As a casual pianist, I often see patterns in life that remind me of those in music. If the past four years of parenting my aging parents have been a variation on the theme of raising our daughter, the recent passing of my father has become a coda all its own. Those final months echoed what came before but presented unique challenges running the gamut from emotional to logistical.

I had hoped to capture the learnings while they were fresh in my memory, but I needed to wait a few months for the pain to dull before sharing. Those last chaotic days proved an emotional fugue. I am still catching my breath.

This was not easy to write and will be a difficult read for many reasons. But this is the guidance I wish I had before I faced the loss of my dad. Bookmark it now, hoping you will not need it anytime soon.

Decrescendo: From independent living to end-of-life care

When you’re amidst it, the decline of a loved one as he or she progresses from independent living to end-of-life can feel gradual and, at times, even repetitive. But looking back, you may notice that the downward trajectory was far steeper than it seemed at the time—especially in those final days. Fortunately, one of the things I remember most clearly about my dad was his sheer “joie de vivre” right up until his last week.

His physical and cognitive health may have been in decline, but the essence of his personality remained intact. Of course, as age and chronic illness take their toll, even the most dynamic people decrescendo. Dad was no exception. Fortunately, with the aid of his electric scooter, he was able to ride my healthier mom’s coattails from my childhood home into an independent living facility, which kept the beat going with a metronome of social activities, restaurant-style meals, and weekly housekeeping, but little in the way of medical care (911 emergency button).

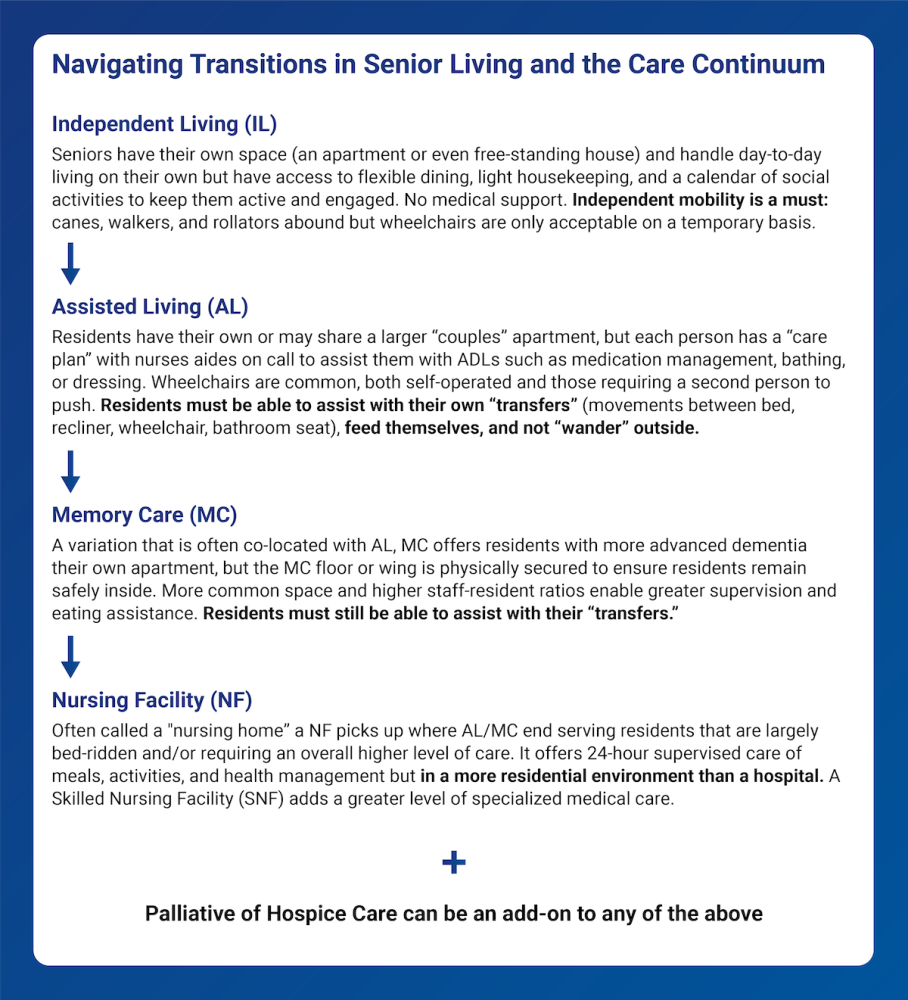

Like a pianist facing the first twinge of arthritis, many of us initially become aware of the disparity between healthspan and lifespan when we can no longer participate in the hobbies, travel, and physically active lifestyle we once enjoyed. But for seniors entering the “care continuum,” health is no longer about watching your HDL or LDL. It’s about your ADLs—the six primary personal care activities of daily living: bathing, dressing, toileting, transferring in and out of bed or a chair, eating, and continence. Your ADLs are the benchmarks that determine your ability to live independently. Living arrangements and medical care become increasingly intertwined as these scores worsen.

To preserve my parents’ independence and quality of life, I sought to keep them together in the lowest level of care as long as possible. My extra “assist” in organizing meds and meals gained them an extra year of independent living. When Mom began to struggle to ensure they took the right day’s meds and gashed herself in several off-balance falls, it was clear they needed more support. Assisted living took over their meds management and provided three meals a day—Mom proclaimed she had finally “retired” at 91! In truth, the growing disparity between my parents’ needs meant she became Dad’s 24/7 nursemaid.

For an aging parent with multiple chronic issues, you may find yourself thrust into the de facto role of a conductor managing disparate specialties as you attempt to determine what is best. While primary care physicians typically take “first chair,” the specialist treating my father’s terminal illness was more effectively positioned to conduct and provide holistic care advice. He became my most trusted advisor.

One of the first things we did was translate Dad’s living will to NC’s MOST (Medical Orders for Scope of Treatment) and companion DNR form (each state has its own) to ensure front-line caregivers and first responders knew his wishes. This helped avoid unnecessary late-night ER visits, supporting our goal of keeping Dad out of the hospital and enabling my parents to live together in assisted living as long as possible.

We focused Dad’s medical care on preserving his quality of life over pursuing aggressive treatments discouraged for his age, legato over staccato. We diligently took preventative measures to avoid new issues—from COVID boosters and flu shots to antibiotics before dental cleanings. The doctor’s palliative care referral added a weekly nurse to monitor Dad’s condition and cut his medical outings in half by bringing X-rays and blood draws for his monthly labs to their apartment. We had a great rhythm going for nearly seven months.

When the assistance of two caregivers became necessary for Dad to get out of bed or transfer from his recliner to a wheelchair, we feared his next move would be to skilled nursing (not offered at his facility). Ultimately, we added hospice care, a necessary last resort to keep my parents together in their assisted living apartment. I’ll admit I was wary. Hospice requires you to give up all existing medical relationships in exchange for an interdisciplinary care team of doctors, nurses, aides, counselors, chaplains, etc., that Medicare fully funds. Hospice has become synonymous with the “last six months” of life. As such, it’s a conversation most avoid for too long: the average length of hospice is three months, but the median is less than three weeks. Dad only received hospice care for 13 days (an unrelated infection exacerbated his terminal illness), but it was invaluable in his final days and passing.

Resonant notes:

- Watch for the signs when independent living is no longer possible and intervene

- Identify a medical quarterback to help orchestrate tough decisions that cut across disciplines

- Translate your loved one’s wishes to the state-appropriate medical scope of treatment forms

- Accept palliative care as soon as it is offered—there is little downside

- Don’t be turned off by hospice’s “final six months” reputation—request a consult (criteria vary by terminal condition) and make informed choices.

Adagio: Last days, final moments

Although Dad’s decline accelerated rapidly during that final week, it felt as if time had stalled, with life verging in slow motion. Perhaps it was my powerlessness in the face of the inevitable after so many months as his advocate-instigator. With the beginning of the end upon us, I was now relegated to watching events unfold rather than shaping them.

In hospice care, ‘transitioning’ refers to the final days or hours in which a person is actively dying. Hospice workers are trained to recognize its signs and are acutely aware of small changes in the patient’s skin tone or timbre of breathing. The hospice nurse overseeing Dad’s care moved up our scheduled check-in to let me know that he probably had less than a week to live.

From that moment, I made plans to spend my nights with Dad and for Mom to sleep in a nearby room. He was on oxygen and painkillers, and I was camped out on a loveseat near his bed, watching and listening. He passed away on our first “slumber party” together.

Shortly before midnight, he took a deep breath and sighed. Then, his labored breathing ended. And almost immediately, his wrinkles disappeared, his face transforming from sickly pale to an angelic glow. I spent a half hour with him. Peaceful, private, and pianissimo.

After checking his pulse with my Apple Watch, I pressed the call button to summon an assisted living staff member who confirmed what I already knew and notified hospice. Before long, the third-shift staff (and even a second-shift caregiver who heard the news and returned) gathered in the apartment, sharing stories of Dad’s witty replies and deep love for Mom. We were so busy reminiscing that the arriving hospice nurse called me to help find someone to let her in!

The hospice nurse became the conductor, declaring the official time of death as the next day due to the late hour. She first called the coroner’s office and then orchestrated arrangements with the funeral home. Typically, they arrive within a few hours to transport the body to a nearby facility until final carriage can be arranged. But so beloved was Dad in my hometown that our funeral director drove the 150 miles overnight, arriving at 4 am to bring him home.

While we waited, I chose Dad’s suit and tie for the funeral but couldn’t find a matching dress shirt. I called and awakened my husband. Peter was a hero in bringing over one of his blue shirts. I drove home at dawn, streets empty, and Dean Lewis’s “How Do I Say Goodbye” on repeat. It was a long night, and I needed some rest. My most challenging task still lay ahead—sharing news of Dad’s passing with Mom, his wife of nearly 64 years.

Resonant notes:

- Set the scene to enable yourself to savor the final moments on those final days

- Lean on the professionals (hospice nurses, caregivers, funeral directors, etc.) to guide you through the steps and family and friends for emotional support

- Apprise the funeral home—and pack a bag ahead of time with your loved one’s special outfit and accessories (e.g., wedding or class rings, book to hold).

Resolution: Logistics following the loss of a loved one

If time slowed that final night with Dad, it accelerated the next morning to reclaim lost moments. Whatever your religion or beliefs, a handful of tasks seem universal: writing an obituary, planning a funeral service or other gathering for family and friends, final disposition of remains, and tying up administrative loose ends. Fortunately, Dad’s wishes were clear. A devout church member, Sunday school teacher, and past Deacon Board chair of the Baptist church where he and Mom married, he had pre-arranged a joint plot in the church cemetery.

As an only child with a grief-stricken mother, all parties immediately turned to me. The main decision I faced was what I wanted to “own” versus what could be delegated to others. I took charge of writing Dad’s obituary and eulogy for his service, a productive way to channel my grief into final gifts to him. But for the rest, I leaned on a trusted local minister and my maternal aunt—she selected hymns, recruited pallbearers, and arranged a reception afterward.

Just before Dad passed, I had enlisted the only funeral home that I knew of in my hometown. But their long list of products and services was overwhelming. To simplify, I asked them to use my uncle’s funeral the prior year as the template and empowered my local aunt to finalize color choices since I was three hours away. I stepped in once when I discovered she was being “upsold” options that tripled the price. My father was a modest man who preferred traditional hymns and his native Appalachian music. He wouldn’t have wanted anything ornate.

The gating factor to wrapping up his business affairs was an official certificate of death (COD), initiated by the hospice nurse and finalized by the funeral home. Amazingly, Social Security happened “automatically” (directly informed by the funeral home), which immediately increased Mom’s monthly benefit. I notified other parties involved in the final settlement of his affairs. Life insurance policies and retirement accounts need the COD to trigger a payout to beneficiaries. Banks and other financial institutions often require it to retitle brokerage accounts, even if jointly owned by a surviving spouse or family member. Equifax, Experian, and Transunion need it to lock the deceased person’s credit file and prevent identity theft.

I emailed Dad’s medical providers through their respective portals, attaching a copy of his obituary. All responded with kind words befitting my dad. Knowing they might immediately disable his profile, I first downloaded copies of his medical records (aka my family health history). Finally, you can’t forget to disable other online accounts. At nearly 94 years of age, my dad may not have been one for social media, but even he had an Amazon account!

Fortunately, my parents had named each other in their wills, so all shifted automatically to Mom. However, probate processes and requirements vary from state to state, so you must do your homework to understand what formal settlement of the will entails.

Resonant notes:

- Be purposeful in choosing what tasks only you can or want to do, leverage others

- Remember that funeral homes are a $20B business; be appropriately skeptical about the need for premium products and services

- Obtain copies of the final COD from the funeral home to tie up financial and legal loose ends—and don’t forget to tend to the digital footprint.

Changing keys

Although Dad passed four months ago, the feelings remain fresh as we work to help Mom navigate her grief anew each week, exacerbated by her own growing health and memory issues. He was the center of her universe. I can only imagine her loss as her lifelong duet has become a solo.

We also had to sort out her new living situation, which amounted to a downsizing within her assisted living facility (coincidentally, to the single above their former couples’ unit). And then there was the matter of my childhood home, which had been dormant since Mom and Dad entered the senior living continuum in 2020. Fortunately, I had started clearing it out and readying it for sale the month before Dad’s passing. I can’t imagine having to do it afterward. With the real estate listing already drafted, we sold it quickly, and Mom’s power of attorney enabled me to shield her from a painful postlude.

Processes and paperwork are one thing. Dad’s personal effects are another entirely. I have boxes of memories awaiting me in my garage—personal keepsakes acquired during over nine decades of life and family artifacts from the house we all once called home. Frankly, I’m not ready to go through them yet—it’ll take a bit more time before I can cherish the memories.